Imagine this: a designer enters a room with what appears to be a tilting blender-totem of a telescope in their hand. It whirs, shakes, and flashes several lights—but, when questioned what it does, the designer has a smile that says, “It doesn’t work yet. But this is how it’ll look and feel when it does.

Now the question becomes—if it doesn’t work, is it still a prototype? Can it be considered a prototype if it does not even serve its intended purpose at all? And more importantly, can such a non-working prototype actually assist in designing a successful product?

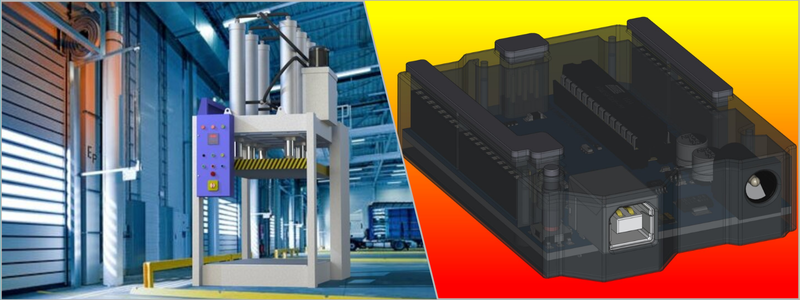

Cad Crowd has worked with many engineering and product companies to develop their products through great prototype design services. Let’s discuss that because the path from an idea on a napkin to a product on the shelf is never a straight line. And prototypes? They don’t always have to work to be useful, although they still have a few things they should do.

The myth of the fully functional prototype

There’s this prevailing myth going around—particularly among non-designers and first-time product creators—that a prototype should work. It should be a full, scaled-down version of the final product. But honestly, that’s more of a Hollywood fantasy than an engineering fact.

In product development and concept design services in the real world, prototypes are like sketches. They’re not necessarily whole, not necessarily lovely, and certainly not necessarily working. But they do one thing very well: they convey. They convey what a thought might be. They prompt discussions with users, developers, investors, and stakeholders. And most times, they deliberately leave space for modifications, because modifications will arrive, whether or not we want them to.

RELATED: Proven Tips to Build a Strong Engineering Team for Your Firm with Freelance Services

Prototypes come in many flavors

Let’s shatter the prototype myth wide open by delving into the various kinds of prototypes. Because not all of them are intended to work—and that’s the plan.

Conceptual prototypes (a.k.a. “Looks-like” Models)

These are entirely visual. Think foam models, 3D-printed models, or even paper sketches. Their task isn’t to function but to signify. They respond to questions like:

- What could this product look like sitting on a desk?

- How will it sit in your hand?

- Does its appearance indicate its use?

This kind of prototype is typical in the early stages of prototype design engineering services, particularly where user feedback on ergonomics or aesthetics is required prior to investment in technical innards.

Functional prototypes (or “Works-like” models)

These actually do work—kind of. They’re typically hideous, perhaps with zip ties and duct tape holding them together, but they do something. They demonstrate that the central mechanism, the physics, the software, or the interaction model works (or doesn’t).

They circumvent the flash. They get rigged up in labs, with off-the-shelf parts, and are utilized by engineers to debug particular areas of functionality.

User experience (UX) prototypes

In digital or hybrid products, UX prototypes can mimic the interaction of a user with a system—clicking buttons, swiping screens, or browsing through a menu. They can take the form of clickable mockups, cardboard virtual reality environments, or even storyboards.

Again, no actual product is being built yet, but you’d be surprised how much insight user testing at this level can generate.

Pre-production Prototypes

These are the closest to the final product—used for compliance testing, manufacturing evaluation, and sometimes investor showcases. They’re expensive, detailed, and (by this point) should mostly work.

But guess what? Even these can fail.

RELATED: How 3D modeling transforms your products with 3D rendering service firms

Prototyping is iteration, not perfection

Here’s the truth: each prototype is an experiment. And experiments aren’t designed to succeed—they’re designed to learn. A prototype that doesn’t work can actually be more useful than one that does if it reveals a flaw in design, prompts a revealing question, or leads to a superior solution.

Many of the most stunning design innovations came out of models that were not functional. Indeed, numerous top product design companies and architecture practices actively foster early failure via rapid prototyping. The principle is to fail early, fail inexpensively, and fail forward.

And this is where having the right question of who you work with comes into play.

Why hiring the right designer (or Architect) matters

If you’re designing a new product—say, a consumer device, an Internet-enabled appliance, or even some compact furniture—design professionals of various stripes are likely to come into the picture at some point. Maybe this includes industrial designers, product engineers, or even architects in the case of actual buildings.

And as soon as you begin recruiting, here’s something you realize in a hurry: firms are not all created equal.

There are some concept-focused—they’re great at doing beautiful drawings, creating stunning casings, and making prototypes that blow clients away. There are some function-oriented—they’ll get the mechanism functional, the tech tight, and the engineering looking pretty.

The best shops? They bring both together. They know a prototype doesn’t have to function on Day 1. It needs to morph.

In architectural design services, for instance, initial physical models are usually nothing more than stacks of cardboard that indicate form and mass. But they have a function: they assist clients in visualizing space, movement, and sense. They’re not structural models. They’re discussions.

In product design, the same rule holds. Good teams understand when to create a looks-like prototype and when to switch to a works-like model. They get the right questions: Are we testing aesthetics, function, or user behavior? Because the answer to that question will decide the type of prototype you actually require.

When “not working” is actually working

It may seem odd, but a non-working prototype can advance a project in significant ways. Here’s how:

Gaining buy-in from stakeholders

Investors, executives, or customers may not like spreadsheets and specs. But give them a clean model they can touch? Or take them through a mock space? That can win hearts and open wallets—even if the model is not yet working.

Getting early feedback

You don’t want to invest $50,000 in tooling only to find out your users despise the feel of your product. A non-functional prototype assists in gathering feedback prior to significant investments.

Identifying design flaws

Ever hear the story about the luggage company that launched a product only to discover users couldn’t open the handle with one hand? A simple mockup could’ve revealed that. You’d be surprised how many oversights are caught with a cardboard cutout or 3D print, not to mention 3D rendering services.

Fueling team collaboration

Having something concrete, even if it doesn’t work, can align teams. Engineers, marketers, designers, and execs can sit around a model, point at it, propose changes, and all use the same visual language.

When does a prototype need to work?

Of course, there comes a time when the rubber meets the road. If you’re trying to validate a mechanism, test a circuit, or debug a software flow, then yes—your prototype must function. But even then, it doesn’t have to be pretty. It just needs to answer a question.

A working prototype is like an experiment in science. It tests or disproves hypotheses. It is not the end product, and it does not have to be pretty. It may be cobbled together with LEGO bricks and Arduino boards—but if it demonstrates that your underlying idea is sound, that’s a major victory.

Lessons from the architecture world

There is a moral from the architecture profession here. When companies are commissioned to create a space, they do not begin by laying bricks. They begin with rough drawings. Then physical models. Then finished drawings. Only after rounds of discussion and approval does construction start.

Some customers want to see a complete plan in Week 1. But savvy companies resist this. They know that preliminary models—even sketchy ones—are key to alignment and discovery.

The same principle should apply to product design. If you’re interviewing a product designer or CAD design engineer and asking for a fully functional prototype at the beginning, you’re not getting it. You need progress, not perfection.

How to know what kind of prototype you need

This is where strategy kicks in. Ask yourself:

- What am I trying to learn?

- Who needs to see this prototype?

- What kind of feedback am I hoping to get?

If you’re speaking to customers, a handsome model will suffice. If you’re selling investors, use polish. If you’re debugging mechanics, don’t care about looks—just get it to work.

And keep in mind: every prototype must give rise to the next one. Keep things simple, develop quickly, and let every version hone your concept.

RELATED: How user-centered design improves product design & new prototypes of your company

Wrapping it up

So does a prototype need to work in order to design a new product?

No. But it has to work for the stage you’re in. A prototype doesn’t need to function as a prototype. It can serve a dozen different purposes—communicating vision, gathering feedback, testing ergonomics, or inspiring investment.

Consider prototypes as stepping stones rather than destinations. They’re question-asking tools, answer-finding tools, and stepping stones forward. And sometimes the best prototype is the one that fails elegantly and directs you to a better path.

The next time someone gives you a prototype and says, “It doesn’t work yet,” don’t shrug. Be curious. Ask what it’s attempting to demonstrate. Because most likely, it’s working just perfectly.

Call Cad Crowd today to obtain a quote and discover the top product prototype designers in the market today.