One of the most important aspects of bringing a new product to market is product pricing. This one seemingly simple thing can truly make or break a product. Unfortunately, how to price a product is usually not the top priority for the inventors or designers that are caught up working out the features of the product, or deciding on packaging options, or doing any of the other myriad things that need to be done. But the price you set for your product can be just as important as any other decision you make when designing it.

Whether you plan to sell directly to customers, to retailers, or to distributors, it’s important to understand pricing and profit margins. Everyone involved has to get their cut, or it won’t work. But it’s a bit more complicated than coming up with prices based on fixed markups from cost. A number of other important factors need to be taken into account. These include:

- The price that they market will bear (what consumers are willing to pay).

- The price competitors charge.

- The perceived value of your product.

- The volume of sales.

- The visibility of your product (how aware consumers are of what you’re selling).

Obviously, this means that product pricing is a bit of a moving target. And that’s fine. Prices can and do change over time. But you have to be very careful about changing prices — whether moving them up or moving them down — and so you want to release your product at the appropriate price point. Which means crunching some numbers.

Understanding Margins

Profit margins are, in the simplest terms, the difference between the amount a product is sold for and the cost of acquiring that product. I say ‘acquire’ instead of ‘produce’ because profit margins are important at every stage of the supply chain. Retailers, distributors, and manufacturers must meet their profit margin requirements in order for your product to be sellable.

Profit margins are often confused with markups. While the two things are closely related, they are distinct, and it’s an important distinction to make in order to price your product properly. The gross profit margin is the amount of profit generated through a sale, while the markup is the difference between the price an item sold for and the cost the seller paid for it.

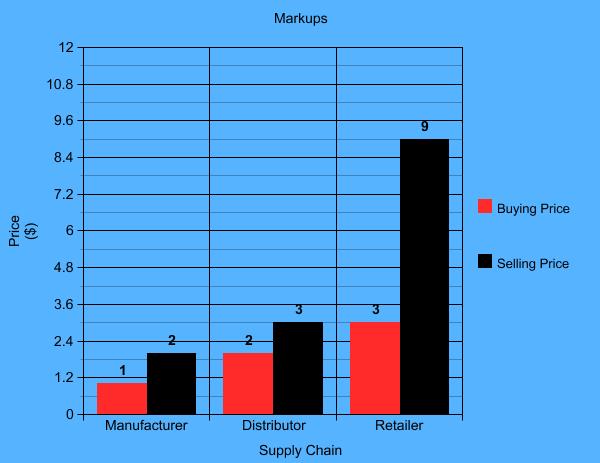

It’s easier to make sense of it with an example. Let’s assume that you are manufacturing your own product. You produce each unit at a cost of $1. You sell these to a distributor for a price of $2. The distributor then sells the product to a retailer for $3. Finally, the retailer sells the product to consumers for $9.

It’s easier to make sense of it with an example. Let’s assume that you are manufacturing your own product. You produce each unit at a cost of $1. You sell these to a distributor for a price of $2. The distributor then sells the product to a retailer for $3. Finally, the retailer sells the product to consumers for $9.

So, let’s consider the markup. The markup from manufacturer to distributor is $2 – $1 = $1, or a 100% markup. The distributor sees a markup of $1, too, but here that only represents a markup of 50%, because the distributor had to pay $2. Finally, the retailer marks the product up yet again from $3 to $9, a markup of $6, or 200%.

Now we know the markups at every stage. But what we really want to know are the profit margins. First we’ll talk about gross margins, and we’ll talk about net margins later. You’re going to want to know the margins for every step of the supply chain because you’re going to have to meet the individual margin requirements at each level if you want to see your product make it to store shelves.

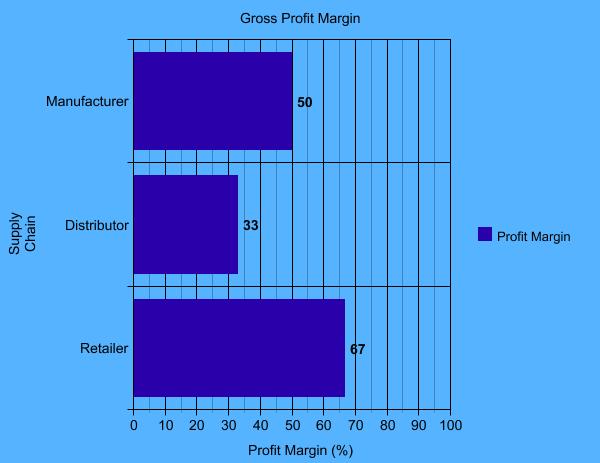

How do you determine the gross profit margins? It’s simple. The gross margin is the markup divided by the price the unit is sold for. Why do we do it that? Because the gross margin is the proportion of revenues remaining from a sale once the cost of the goods sold is accounted for. Make sense? Let’s go back to our example.

Th e manufacturer (you, let’s imagine) has a markup of $1, and sells the product for $2. 1/2 = 0.5, and so we have a gross margin of 50%, a very simple example.

e manufacturer (you, let’s imagine) has a markup of $1, and sells the product for $2. 1/2 = 0.5, and so we have a gross margin of 50%, a very simple example.

The distributor also has a markup of $1. But they are selling to retailers for $3. 1/3 = 0.33, which means the distributor here has a profit margin of 33%. Notice how, even though they are making $1 per sale just like the manufacturer is, their profit margin is significantly lower.

Now let’s look at the retailer. They have the biggest markup, at $6, and they sell to consumers for $9. 6/9=0.67, for a profit margin of 67%. Notice how that actually isn’t much higher than your margin of 50%, even though the actual dollar amounts are much higher.

This is very important. People often see retail markups of 100% or more as being outrageous, but that’s because people tend to confuse markups with profit margins. Retailers are taking on more risk to carry a product: they have to pay more for it and it takes up valuable space on their shelves. If consumers don’t end up buying anything, retailers have the most to lose, financially speaking, from dead stock. In this case, the retailer has a 200% markup that yields a 67% profit margin, which is actually a very reasonable profit margin for a retailer.

Minimum margin requirements will vary significantly from one type of retailer, industry, and price point. However, retailers will often require a minimum gross margin of 50%. Distributors vary as well, but typically require a lower margin somewhere between 20% to 40%. Your goal is to price your product so that you can meet those requirements, while still making enough money to support your business.

Net Profit Margin – the Floor

Gross profit margins are important, but they leave a lot out, since they account only for gross profit and revenues. But there’s more to the actual cost of a product than the sale price or the cost of manufacturing. As a business, you also need to account for your overhead costs. This includes things like rent, building upkeep, wages, shipping costs, technology costs, utilities bills, stocking fees… It can add up. All of this needs to be accounted for when determining the real cost of your product.

You need to be able to price your product high enough that it allows you to cover your real costs, while also allowing your distributors and retailers to hit their required profit margins. Your net profit margin is your pricing floor — you can’t go below it, or you will be bankrupting yourself.

This gives you the three main targets you have to hit in order to have a viable product:

- You are selling at or (preferably) above your net profit margin floor.

- Your partners in the supply chain are able to hit their required minim gross profit margins.

- Consumers are willing to pay the final retail price for your product.

You need to hit all three of these goals. Miss any one of them, and your product is not marketable. There’s no point in getting 1 and 2 if consumers won’t buy the product, and there’s no benefit to you of satisfying your partners and consumers if it drives you into bankruptcy.

Meeting those three hard requirements means your product can be sold. Determining the exact price can be a bit more of an art than a science. Picking the right price can mean the difference between success and failure.

Under Pricing

There is always a strong temptation to sell your product for the lowest price that you can while satisfying the three main requirements listed above. If your price is lower than your competitors, you can gain an edge over the more established competition and make up for the lower sale price with a higher volume of sales.

That can be true, sometimes. But under pricing is very risky. Trying to entice consumers with low prices can backfire badly by creating the perception that your product is cheap. This can damage your brand value considerably, depending upon the nature of the industry you are operating in.

People tend to perceive expensive things as being nicer than cheap stuff — even when they are exactly the same! Look at bottled water, for example. Or the world of fine art. Pricing can’t just be a race to the bottom, because many consumers will perceive the higher cost items as being automatically better than the cheap alternatives, even if there is objectively no difference.

This is not to say that you should never lower prices, but be very careful and strategic about trying to undersell your competitors, as you may end up alienating your own customers.

The other risk you run is for your competitors to take notice of your strategy, and to beat you at your own game. Bigger players with better-established distribution channels can probably beat you on price if they want to — they might even be able to operate at a loss if they perceive your product as a threat.

Over Pricing

Over pricing can also be a problem because the consumers will see that your competitors are offering the same thing for cheaper. Maybe your product actually is worth more than the competitors. If that’s the case, you still have to be careful not to exceed what the market is willing to bear.

Pricing is a moving target. There are many factors at play, including your own business goals. Are you trying to achieve market dominance through razor thin margins, or are you happy selling a lower volume but at a higher price? Do you want your brand to be associated with high quality, or with bargain prices? These kinds of attitudes will help you determine the appropriate price for your product.

Market Research

In addition to the number crunching we’ve talked about already, you need to do a bit of market research to help you understand both your consumers and your competition. This can range from informal surveys of your existing customers to professional market research analysis.

If you can, get feedback from real or potential customers about their perception of your price — whether they find it fair, low, or too high. You also want to determine what your target demographics are so that you can cater your product pricing to your audience. If you’re primarily going to be selling to college students, then you probably won’t want to price your product as a luxury good. If you’re trying to sell to up and coming urban professionals, though, you’ll want to sell a high-value product.

You also want to understand your competition. How comparable are their products to yours? What are their prices like? Usually, comparable competitors are a good reference point for pricing your product. You can get away with a higher price either if your product is perceived as higher quality, or if you offer additional services/features that the competition does not. This can be things external to the product itself, like customer service or a local presence, but you have to actually be able to deliver on those features.

If you can, try to compare the real prices between your product and the competition, rather than merely the sticker price. Getting insight into your competitors’ margins can be difficult, but also very informative when it comes to pricing your new product.

Cad Crowd is here to help with any of your product design and development needs! From industrial design to contract manufacturing, we’ll connect you with the expertise you need to create the best product at the right price. Get in touch today for a free quote, and tell us how we can help you.